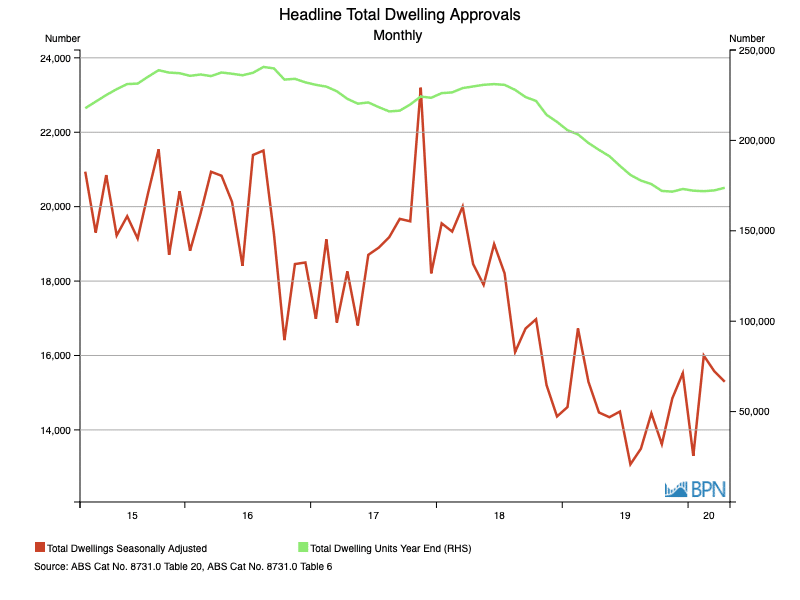

Despite expectations of a major fall in dwelling approvals in April, the pipeline of commitments fed more supply into the market, with a total 15,294 dwellings approved, on a seasonally adjusted basis. Down just 1.8% compared with March, the April result fed into a year-ending total of 173,802 approvals, up 0.3% compared with the prior month.

However, the approvals data was a momentary surprise only, with the immediate realisation that the anticipated slump in approvals is not avoided, just pushed down the road for a month or more.

As a consequence, attention shifted from the ‘yada yada’ of headline approvals – shown in the chart below – and focussed on some other measures. There is plenty to cover, so we will start by looking at some of the state level approvals, then turn some attention onto house prices and address some of the strategic arisings.

Fig. 11

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

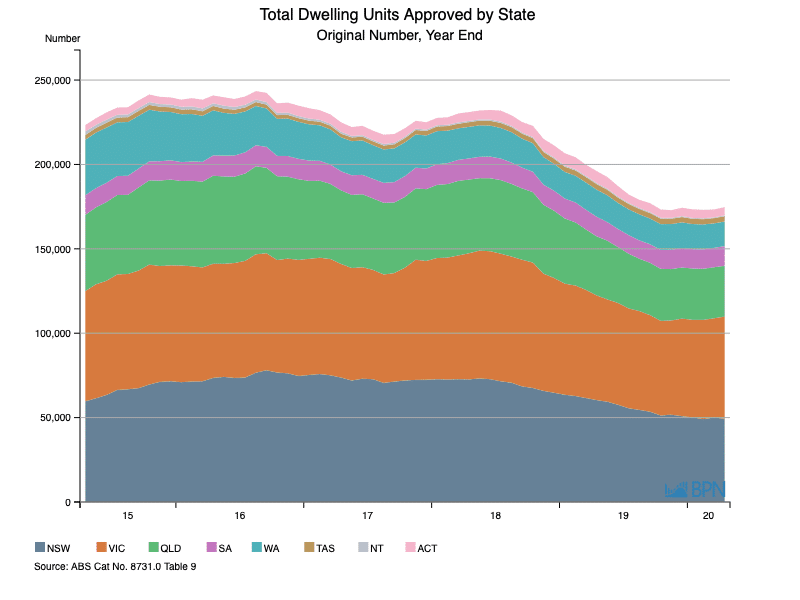

We rarely have the real estate to drill into state level dwelling approvals, but when we focus on this aspect of dwelling approvals, we can see that the last year has exposed some major differences between Victoria and New South Wales, in particular.

The chart here shows total approvals by State, on a moving annualised basis.

Fig. 12

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

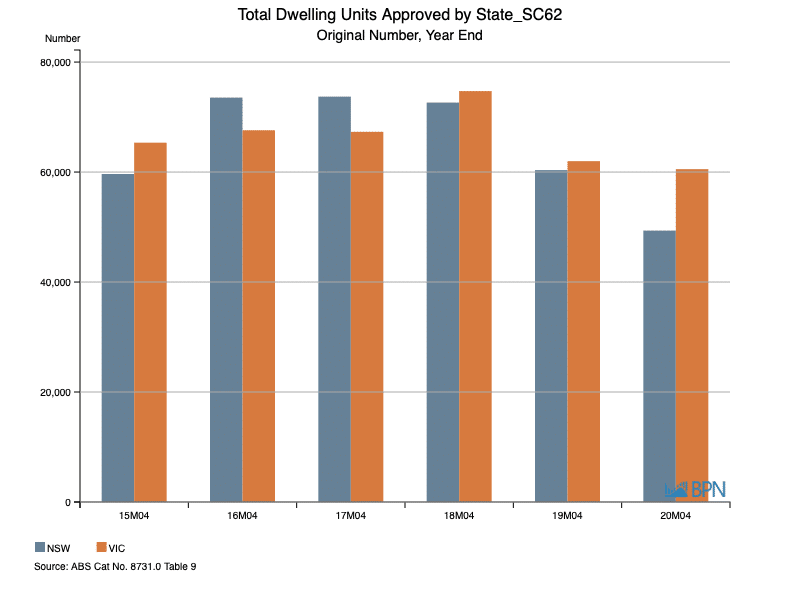

Year-ended April, New South Wales recorded 49,357 total dwelling approvals, down 18.2% on a year ago, and declining 1.3% compared with the prior month. Meantime, Victoria saw total dwelling approvals reach 60,520 units, down just 2.4% compared to the prior year, and up 2.9% on March.

The chart here shows this noteworthy data as a direct comparison between the two big states, over the last six years. We can see that for four of the six years shown here, Victoria experienced higher approvals than New South Wales. To a large extent, this data shows the outlook differences between the two states, from a population perspective at least.

Fig. 13

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

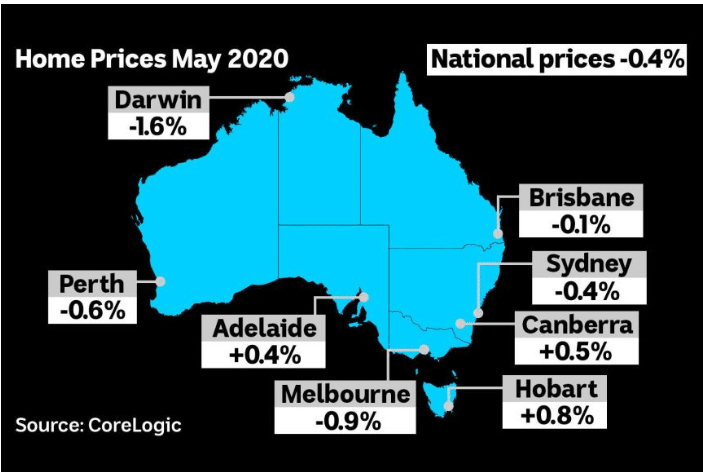

New house developments are one thing, but we also need to consider the price at which housing is being sold. In May, house prices were relatively stable, with the ABC’s Michael Janda reporting average capital city price declines of just 0.4%. That said, the results were patchy around the country, as price movements ranged from -1.6% (Darwin) and 0.8% (Hobart).

Perhaps most significant, prices in Sydney were down 0.4% and in Melbourne, 0.9% lower.

Fig. 14

Source: CoreLogic data on the home price changes for Australian capital cities in May 2020. (ABC News: Alistair Kroie)

Prices are unlikely to hold on, according to commentators, because many home-owners are taking advantage of mortgage holidays that will end in September or thereabouts. After that, distressed households may be forced to sell.

Already under stress in many cases, investors have begun exiting the market, selling investment properties at a faster rate over recent months. The long-term average of rental properties is 9% of all dwellings being sold, which had risen to 11% in early May. That does not seem like a lot, however we also need to consider the fact vacancies are surging (up 2% in April according to SQM Research) and rental rates are falling.

All those factors imply there will be less investor activity in coming months. That could, as Nila Sweeney wrote in the Australian Financial Review, mean that developer driven multi-residential developments will be difficult to sustain until conditions improve.

The housing outlook is therefore more than a little grim into the future, especially when we consider that interest rates are at historic lows. Loans are historically cheap to service right now.

As Michael Bleby wrote in the Australian Financial Review in mid-May, the expectation had been that the relative weakness of the housing sector through 2019 would push the market to the brink of structural under-supply, relative to demand. That would have caused a new round of construction activity – especially for apartments that rely on supply and demand balances to be at their most viable – late in 2020.

But the pandemic has pushed that down the road also, with muted demand and an increase in rental availability brought on by lease repudiations and increased dwelling sharing.

Linking the local and immediate demand for accommodation with stalled population growth, reduced investor sentiment (both domestic and overseas), Bleby reported industry expectations that apartment and multi-residential property development in general will not rebound until 2022 and 2023.

Leading building supplies firms have taken heed of these conditions. Diversified materials supplier CSR announced it was scrapping its dividends as it battened down the hatches for what it anticipates will be a very tough second half of 2020. In late May, Fletcher Building announced it was reducing its workforce by 1,500 (500 in Australia) as it braced for a sharp downturn until at least the middle of 2021.

For the housing economy at least, the conditions and expectations of many in the sector suggest that a ‘V shaped’ recovery is an unlikely proposition.