Much discussed, the state of the Chinese economy now seems to take up as much time on the evening news as the domestic economy. There is a simple reason. Whether it is Australia or many other countries, China is so much the main game, in some respects, it is the only game in town. That is why China’s super

Fig resources boom in late 2016 was so important, with prices rising and carrying through until very recently. Now however, there are signs that rally is declining, contributing to new concerns about the Chinese economy.

The ANZ Bank’s Chief Economist for China, Raymond Yeung forecasts that momentum through the remainder of 2017 will slow, led by declining new orders, which themselves are showing through in lower input prices.

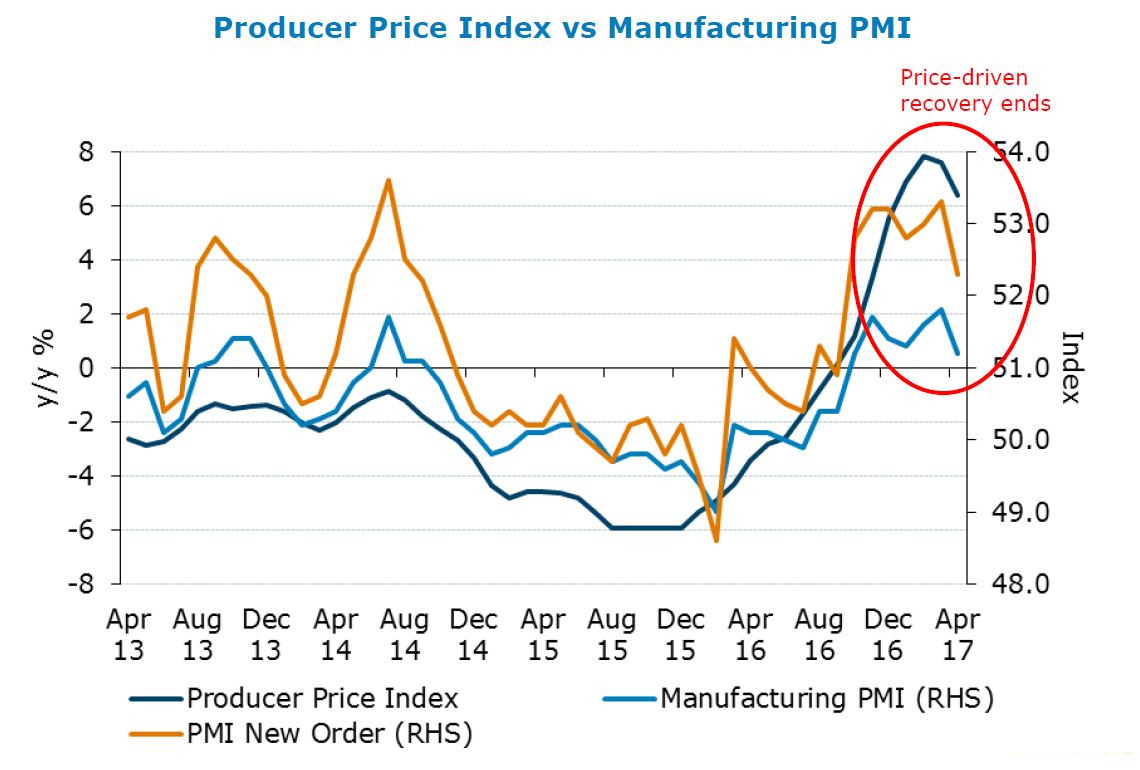

This is reflected in the Chinese Producer Price Index (PPI), which as shown below, fell 0.4% in April, as the Performance of Manufacturing Index (PMI) declined similarly. The chart is doubly useful because it shows the impact of the prices rally and commodity boom in late 2016, as well as its recent slump.

Yeung points to an easing of tensions between China and the USA as economically useful for maintaining external demand, which will keep China in surplus with the US for plenty of time to come. That means China’s risks are largely internal, at least currently.

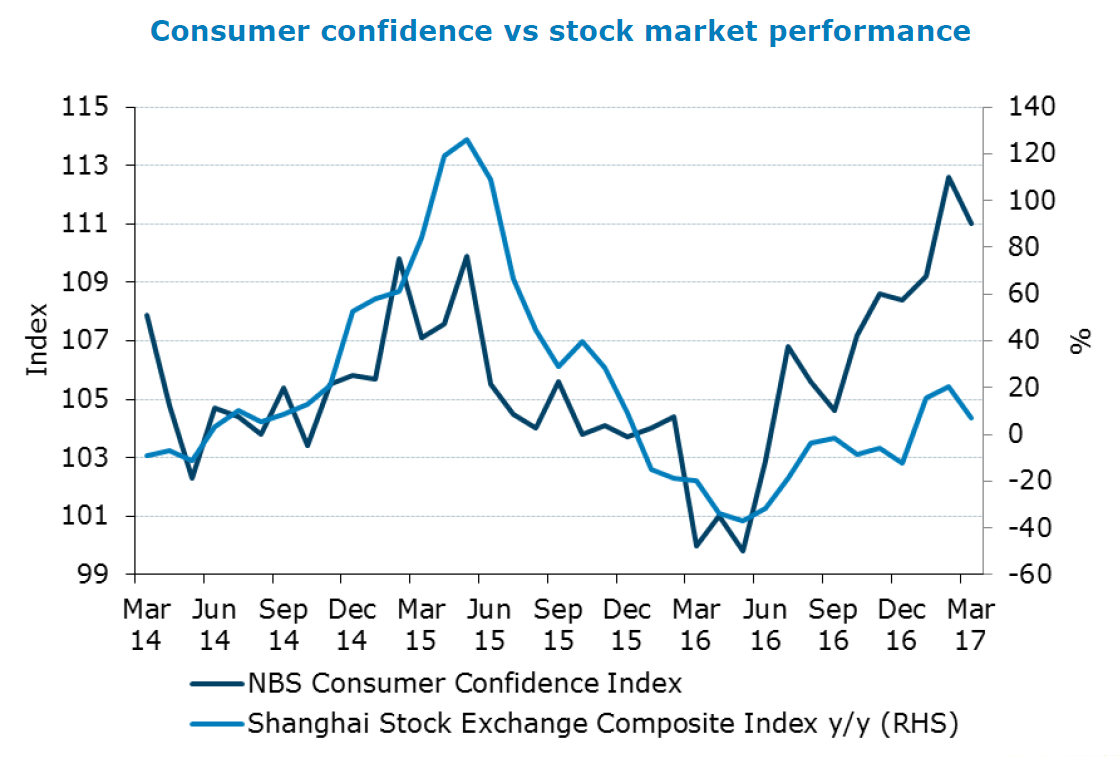

Risky investment products have helped push the Chinese 10 Year Bond rate up by 30 basis points since April, which has flowed through to a steep fall in consumer confidence, along with the risks being factored into the Shanghai stock exchange, as the chart below shows.

However, consumer confidence remains crazy high and for political reasons, will remain that way until at least year-end.

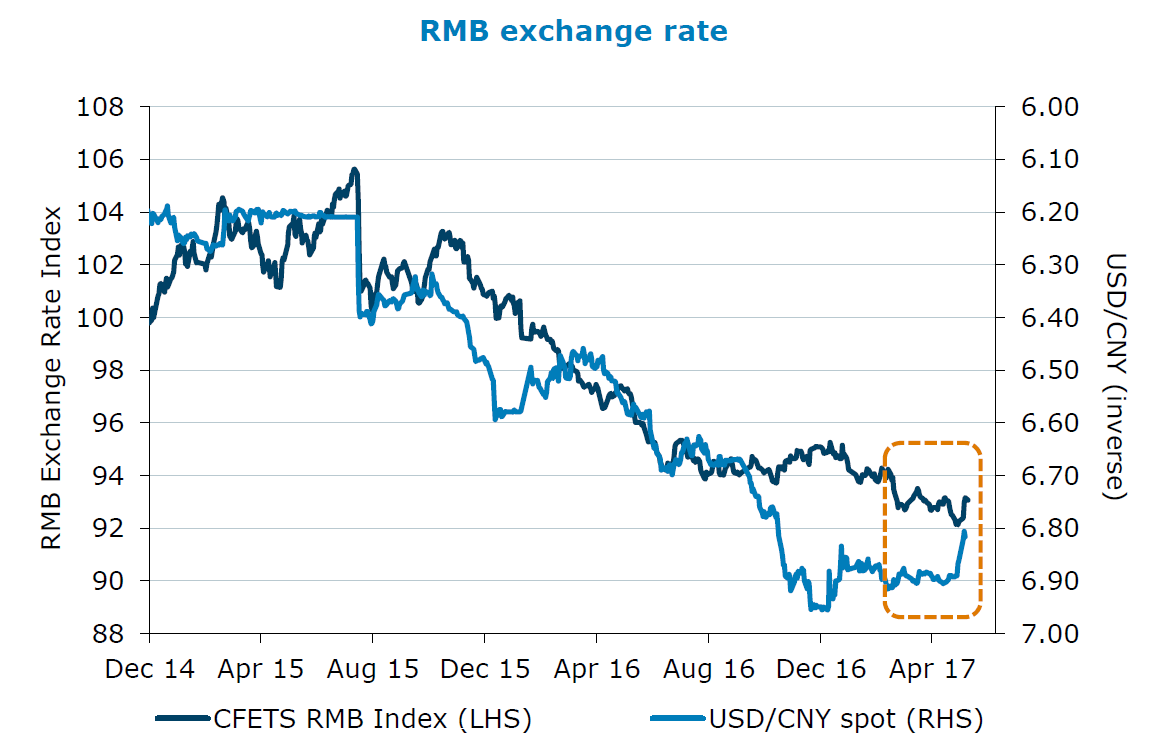

A further sign of risk in China is the addition of new balancing controls on the Yuan’s exchange rate with other currencies, especially the US Dollar, of course. Beijing is seeking to have more control over the exchange rate, as it seeks to ensure it maintains its positive capital flows, potentially at levels above those that are sustainable.

We can see the effect in the following chart.

In sum, as Yeung says, the risks in China are growing, including the risk of a policy shock that plays to domestic needs, at the expense of everyone else.

It might be that the commodities boom into China was short-lived in 2016 and early 2017. It certainly came as a surprise. There seems little likelihood of a counter-surprise until very late in 2017, and even then, there is no certainty or real clarity on what the manifestation of the risks might mean for Australian suppliers.