Modest though it is, Australia’s annualised GDP growth of 1.7% year-ended September 2019 is at least growth. There are many doubts about the robustness of domestic economic conditions right now. One of the factors causing concern is that economic growth – such as it is – is being driven by sectors that are typically more volatile and cyclical, and less by factors that are more structural.

Statistics Count has allocated the contributors to economic growth into two groups. The first is household and building and the second is government and business.

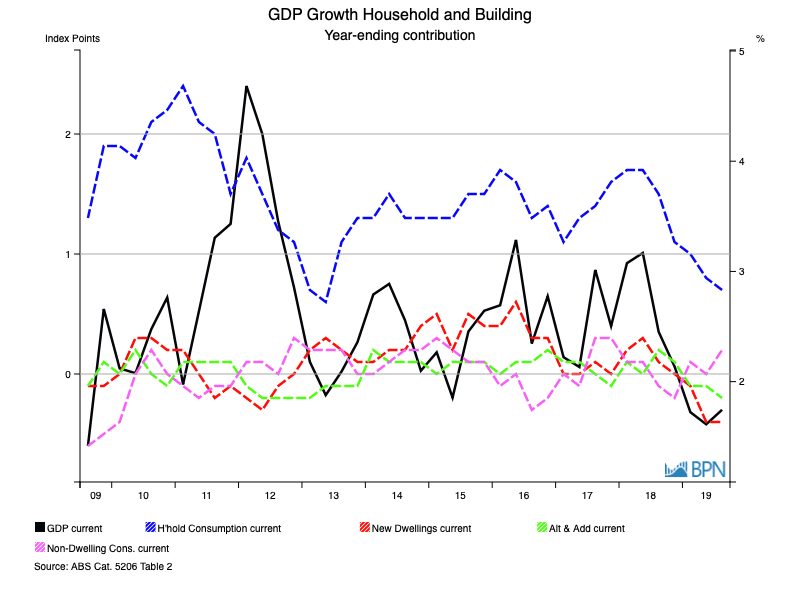

The household consumption and building expenditure sectors are displaying precious little about which we can be confident. The chart below tapes out their particular tale of woe, with year-ended September GDP shown in black, at its paltry 1.7% (charted on the right-hand side).

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

Overall, the really concerning feature of this chart – from an economic growth perspective anyway – is that household consumption has plunged to annualised growth of just 0.7% (charted on the left-hand side).

Why is this such a big concern?

Because traditional economic models measure outputs like expenditure, and the household sector is the largest single contributor to the total economy. When it underperforms, it drags the entire economy down with it.

Moreover, the July tax cuts (which are now flowing through) made no difference to household consumption. The punters, one might say, shoved the extra dough straight into their deepest pocket, or more realistically, onto their largest or most pressing debt. Retail sales data demonstrates they did not pull it back out for Christmas either.

It is difficult to escape the now regular discussion on soft or weak wages growth in the Australian economy, but when wages are not growing, it is difficult for household consumption and general economic (GDP) growth to follow.

While it may be languishing, at least household consumption is positive. So too is non-dwelling construction, which lifted its head above water to record an under-whelming 0.2% growth over the year-ended September 2019.

But new dwelling expenditure and alterations and additions both detracted from GDP, falling by 0.4% and 0.2% respectively, over the year. Each of these results is to be expected, given the housing downturn. There are some green shoots in latest housing finance data, as the next item in Stats Count outlines, but it will be a while before they make much of a contribution to the nation’s economic growth.

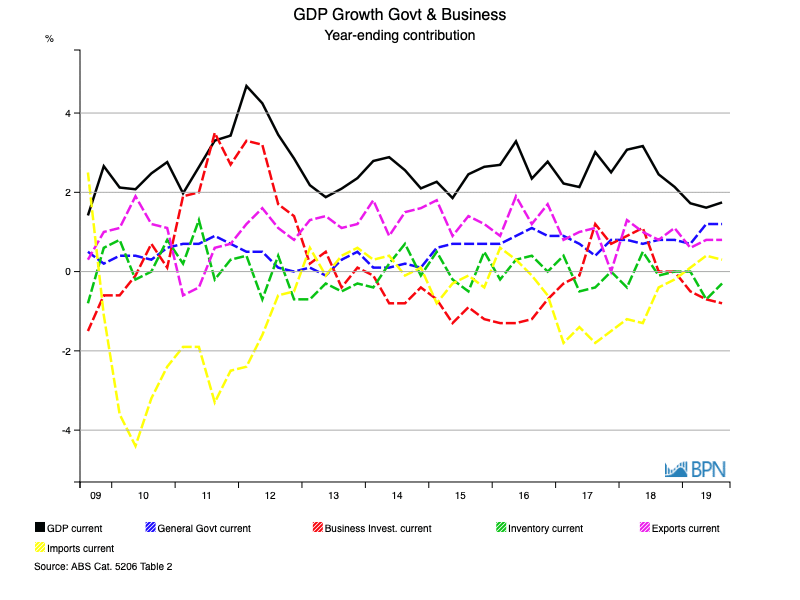

Turning to the government and business sectors, we can see immediately that there are a couple of the sectors that are pretty much always contributing to GDP growth. The first and most prominent is shown in blue – general government expenditure. Its contribution grew 1.2% year-ended September, rising as natural disaster and healthcare costs grew. Exports (+0.8%) also added to economic growth, in typical measure. To some extent though, that is counter-weighted by imports that by growing 0.3% over the year, detracted from GDP by that amount.

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

Other detractors from growth included inventory (-0.3%), which means an increase in the value of goods produced but unsold.

However, it is hard to avoid examining the role of business investment in dragging GDP down by 0.8% over the last year. Shown in red, it has averaged a contribution of just 0.2% per annum, meaning that business investment has rarely been a domestic positive. When it has been, it has observably been short-lived.

There is a lot to analyse before one can be conclusive about the cause of sub-optimal business investment. Suffice to say at this point: for a series of reasons, despite the availability of cheap debt over virtually all of the decade, there has been insufficient confidence and inducement for businesses to invest in a manner that has stimulated economic growth.

There are emerging signs of some key economic criteria flattening out, but there are others that still present a downward face. The December quarter GDP data will be telling in this respect.

If the downturn deepens, if a saving grace like mining exports falters, and the Government fixates on its surplus over the alternative of expenditure to stimulate the economy, economists will dust off the ‘R’ word (not used since 1993 – not even during the GFC). That would put a dent in confidence!

Should the evidence of contraction continue to mount, we would watch for the RBA to flex its remaining orthodox monetary tools in February (interest rates). Then we would hang on for the prospect of more adventurous efforts from the central bank (including quantitative easing) thereafter.