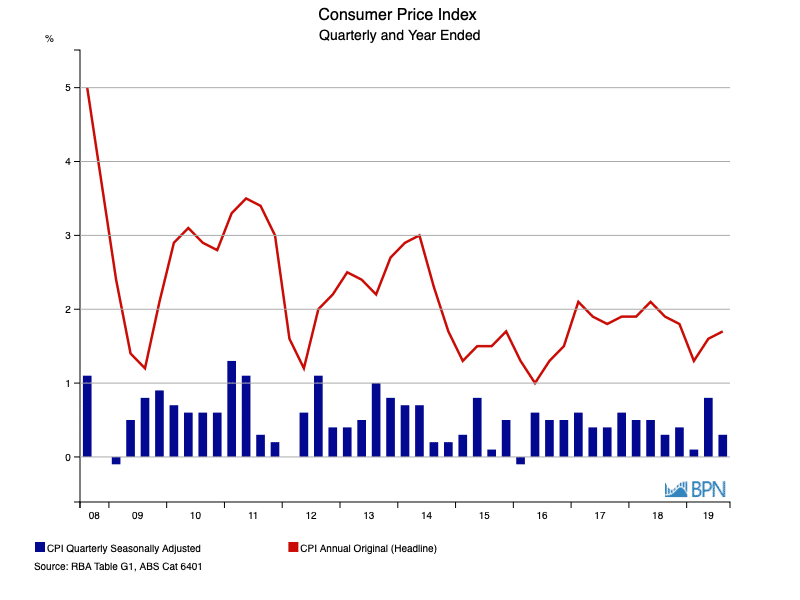

Australia’s underperforming demand and consumption related indicators continued to slide sideways and remained below the national target over the year-ended September. Inflation – measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was an anaemic 1.7%, while the Reserve Bank of Australia’s preferred measure of core inflation was at its historic low of a sickly 1.4%.

Even a relatively strong 0.5% inflation figure for the September quarter did little to assist the CPI to raise its head to the target minimum of 2.0% per annum. That is little wonder, because as the chart below shows, quarterly inflation has been lack-lustre for several years.

Fig. 18

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

The reason Australia’s inflation and consumption driven demand continue to scud along the bottom of the vaguely acceptable (at least we are not in a recession) are pretty widely understood.

Australian households have their expenditure cue in the rack while they work to service or pay down debt. Even though low interest rates prevail (and are getting lower), wages growth is also slow, leaving the average household little wriggle room to grow their expenditure and thus, assist inflation to grow a little stronger.

As Greg Jericho pointed out in The Guardian, the situation is perhaps a little worse than even the headline data suggests. Other than tobacco products, September quarter inflation was fuelled mainly by expenditure on recreation and culture and clothing and footwear. He lays that out in the chart below.

We might argue that if items of a discretionary nature are seeing higher expenditure that people are opening their wallets more, right?

But as Jericho writes:

“Well, no.”

“The big increase among recreational and culture items was international travel prices – up 6.1% in the September quarter alone – and the increase in clothing and footwear occurred not due to a big jump in people buying such products but for the same reason for the increase in the price of international holidays – the falling Aussie dollar.”

That is an ‘ouch’ moment for the domestic economy because what that means is both that there is little underlying strength to the domestic economy and where consumption has grown, it is higher expenditure on potentially the same amount of goods and services.

The lower Australian dollar is generally good news for the domestic economy and for exporters, but it is not of itself a very satisfactory measure of the health of that same economy. It just helps.

We will need to wait until the economic growth – Gross Domestic Product – data is available for the September quarter to really assess the effectiveness of lower interest rates and the much-vaunted tax cuts on expenditure levels and inflation. However, the latest news on that front is the average Australian household has been receiving around $400, not the estimated $1,000. That is not a lot of stimulus, when all is said and done, so don’t hold your breath for a stimulus fuelled return to growth in demand.