Every economic cycle is different. In any other circumstances the employment and wage data reported in September and October would be regarded as amazing and entirely good news. In October, the unemployment rate was 3.7% and in the September quarter, wages were up 1.3% for the quarter and 4.0% for the year.

The very minor increase in unemployment is relatively insignificant and still sees the unemployment rate at levels not seen for fifty years. Wages growth was its highest in twenty-six years.

Normally this would be employment nirvana for households: everyone has a job and wages are growing. However, with inflation creating cost of living challenges for households and the impact on mortgage holders of interest rate rises to curb inflation, households are doing it tough. The pandemic may have been a profitless boom for many businesses, but the employment boom is sending many households backwards.

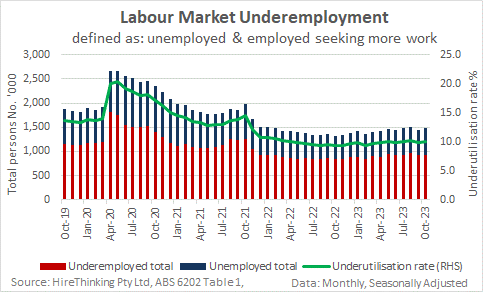

Reflecting the strong labour market, the underutilisation rate – the combination of unemployment and underemployment or those seeking more work – lifted 0.1% to 10.0% in October, 3.9% lower than at the start of the pandemic in March 2020.

Underemployment remained at 6.3% in October. While this was 0.4% higher than October 2022, it was still around 2.4% lower than before the pandemic.

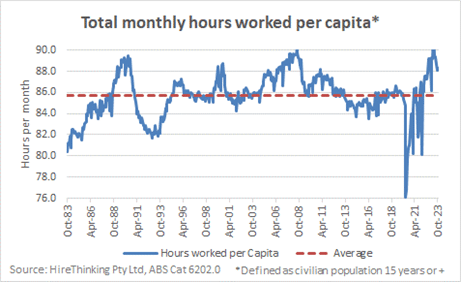

Consistent with this stellar data, total hours worked were up 0.5% in October 2023, similar to the employment growth of 0.4%.

However, the rate of growth in hours worked is slowing, suggesting that the labour market might be starting to ease after a particularly strong twelve-month period. No wonder really with every possible unit of labour deployed across the economy.

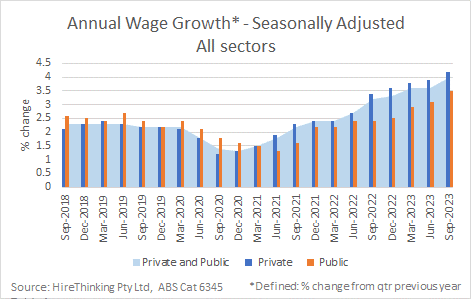

Flowing in part from strong employment – and a lot from inflation and pretty solid profit data – wages growth has been positive and is assisting households to cope with the much vaunted cost of living pressures.

ABS analysis provides a detailed insight to the events that delivered the wages growth. Michelle Marquardt, ABS head of prices statistics, commented:

“A combination of factors led to widespread increases in average hourly wages this quarter. In the private sector, higher growth was mainly driven by the Fair Work Commission’s annual wage review decision, the application of the Aged Care Work Value case, labour market pressure, and CPI rises being factored into wage and salary review decisions. The public sector was affected by the removal of state wage caps and new enterprise agreements coming into effect following the finalisation of various bargaining rounds.”

Wages growth increased this quarter across each of the different methods that set pay. Jobs paid by individual arrangements delivered the largest portion of wages growth, with remuneration governed by awards and enterprise agreements also contributing more to wages growth than historically seen in a September quarter.

As Greg Jericho explained in The Guardian, the wages increases for the quarter were structurally quite sound, as they were centred on the lowest paid workers. Good for their households and as the lowest paid save the least, more likely to be out doing good in the economy than growing fluff and earning interest in bank accounts.

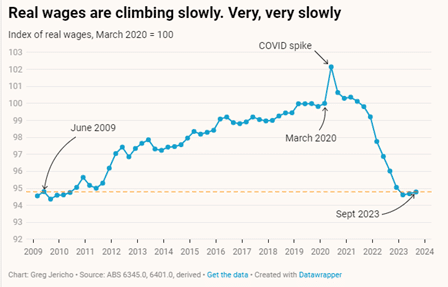

There is a sting here though – its economics, there is always a ‘yes but’ – and the main sting is that in real terms, wages have barely moved after slumping to levels not seen for fourteen years.

Jericho’s chart, reproduced below, demonstrates that the spending power of the household wage is, on average, about the same as at the bottom of the GFC.

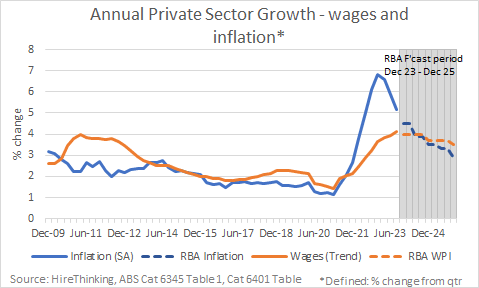

As part of the soft landing referenced elsewhere in Stats Count, the outlook for wages and inflation is critical if households are to make ‘real’ gains and start getting ahead of cost-of-living challenges.

Shown in the chart below, recent RBA forecasts have the cross over point being reached in early 2024.

Given the savings buffer built up during COVID is now exhausted (refer elsewhere in this issue of Stats Count) it will be important that this forecast is met, allowing for household spending to remain in positive territory, thereby supporting some level of economic growth next year.

All this highlights how interconnected the elements of the economic puzzle remain!

There is something structurally peculiar in an economy where everyone has a job, hours worked are at their upper limits, wages are growing and yet the capacity to buy nice things is diminished.

There are two factors we might look to that can explain some of this unhappy trend.

First, as we discuss elsewhere in this edition, dwelling prices and associated debt (and by extension a lack of supply) see households putting more and more of their income to fund their housing needs, with higher interest rates really hurting.

Second, no matter how much labour we toss into the economy, its utilisation appears pretty ineffectual, at least marginally. We have to consider that years of under-investment in the non-mining sectors is cruelling the capacity of the workforce to be more productive. We will not bang on too hard about this just now, but that is highly inflationary because every additional unit of input (labour) is producing less output.

In that context, lower unemployment and higher wages are good, but also bad, because they are symptoms of an economy that is overdue for significant micro-economic reforms.