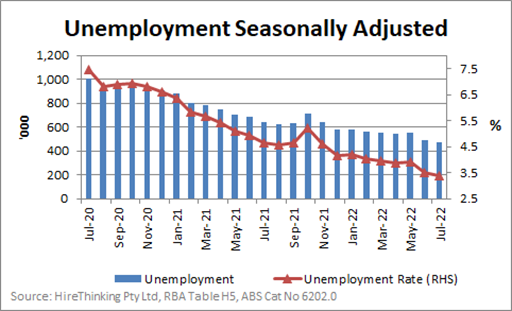

Australia’s unemployment rate dropped to a remarkable 3.4% in July 2022, as all the indications are Australia has reached – and potentially exceeded – the primary definitions of full employment. Labour supply has serious implications for the economy, so its little wonder as the unemployment rate plummeted, the nation’s leaders summited.

The Jobs and Skills summit has just concluded, and while the dust must settle for analysis to be complete, there are some big take-outs that point to the dire state of labour supply for Australia.

First, the skilled migrant intake will rise by 35,000 people per year to 195,000 people per year, commencing immediately. We hear the posturing about this being a short-term measure, but Australia lost around 350,000 migrants over the pandemic. This measure will last a decade or more, if we are any judge.

Second, pensioners will be able to work and earn more before losing any of their pension or associated rights. That’s good news, but it’s a relatively minor concession to the bleeding obvious and there are still some bureaucratic loopholes through which retirees will have to leap.

It’s important to note there were other initiatives that seemed to have a high enough level of support to ensure they are implemented. Some we’ll cover briefly in the item on wages in this edition of Statistics Count.

The two points above are important because they go fundamentally to the question of labour supply, which is operating under extremely straitened conditions right now.

In the first chart we can see the unemployment rate continuing to motor its way down to the current level of 3.4%, with 473,600 people unemployed.

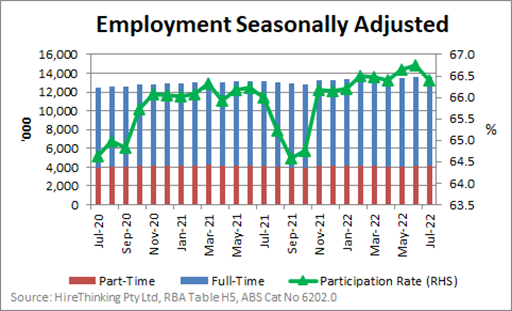

In a slightly perverse indicator of the limits of economics, though the unemployment rate dropped, the number of people in employment also fell, taking the participation rate down to 66.4%, which is still incredibly high, as the chart below shows.

How does that happen? Employment fell 40,900 people as about 87,000 people left full-time jobs and about 46,000 entered part time jobs. Some of those people who left work were not ‘in the labour market’ during the month, so the number of people in work or seeking work actually fell. That’s a labour supply problem right there.

As we reach full employment, these slightly perverse outcomes will be more common – a stressed system will respond in peculiar ways.

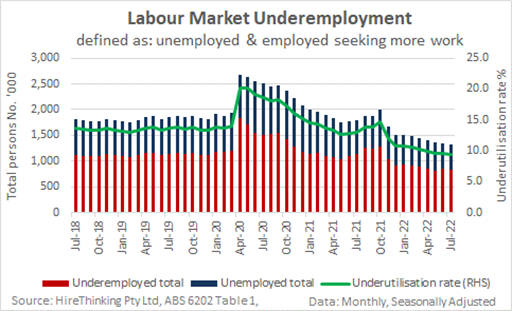

Let’s compound the ‘system under stress’ scenario by observing the number of people underemployed (those either unemployed or seeking more hours) fell about 37,000 people and the underemployment rate dipped to 9.4% as we can observe here.

It follows that if the number of people seeking additional work has fallen, the nation is probably working more hours on a per capita basis than during the pandemic. And lo and behold, that is the case, with the trendline pointing up, as we can see below.

This is interesting data to ponder, because it shows the average number of hours worked is rising but is well off the crazy heights of the pre-GFC.

What is occurring is more people are getting work at the moment, and on average we are working a little more, but we still have a demonstrable and agonising labour shortage. What’s going on with that?

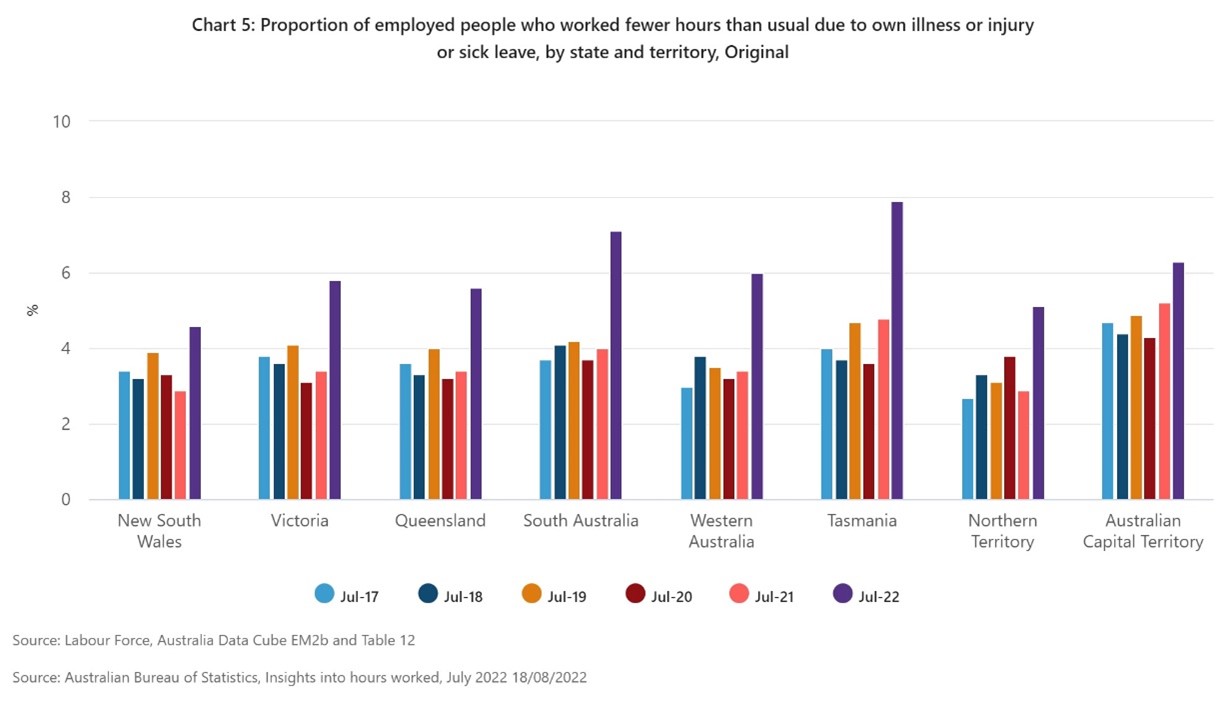

That’ll be the long tail of the pandemic, rearing its nasty head again. The impact of the third wave of COVID 19 (though it seems more a punch than a wave) was particularly harsh in July, as we can observe below and as Georgie Moore Long observed in the Australian Financial Review in August.

Moore Long reported Treasury as estimating in 1H22, Australia lost 3 million productive work hours to COVID 19, with the example being June when around 31,000 people per day called in sick due to COVID 19!

There is no sugar coat here. A full employment economy brings benefits, it brings stresses, it brings strange data and eventually, via migration, improvements in productivity and some more innovative thinking on labour supply, it brings relief.

An anxious economy awaits a labour replenishment.