In an utterly disrupted world, many forecasts have fallen apart, precisely because the assumptions on which they rely have been smashed by divergent experiences. As the RBA found during the pandemic, that meant its assurances – for example – that interest rates would not rise until 2024 (subject to a number of caveats) was utterly incorrect. Here we take a short look at why forecasting is so challenging, and ultimately, just another input to business-level decision making.

In an internal review of its ‘forward guidance’, the RBA recognises its expectation inflation would stay with the target 2-3% bounds was incorrect and that resulted in it needing to lift interest rates sharply over the course of 2022. A link to the review can be found at https://www.rba.gov.au/monetary-policy/reviews/approach-to-forward-guidance/index.html

While the review takes on board some criticisms (and makes some of its own about itself), that is not the main point of the review.

Ultimately, the review finds that the disrupted input information during the pandemic skewed the traditional modelling results, that too much emphasis was placed on the guidance by the media and other commentators, that the RBA itself needed to find ways to have its more subtle ‘state-based’ feedback adopted in the economy and so on.

This is an intriguing review because as much as it responds to the limitations of its own forecasts, it also responds to the propensity of the commentariat and by extension, the public, to adopt the forecasts and even the more nuanced guidance as holy writ. As though somehow, if the RBA says it may be so, it is safe to assume it will be so.

Worse, of course, when the forecast turns out not to be completely accurate, the RBA is criticised as though its running a baseless crypto-currency exchange, not pulling the levers and pushing the buttons on a sophisticated and multi-trillion dollar economy.

Little wonder forecasting is described as a ‘mug’s game’.

For reference, the RBA outlines the basis on which it will provide future ‘forward guidance’. It will consider:

- Qualitative or narrative guidance (not numbers) and only over the near-term

- Whether to provide interest rate guidance or not

- Publishing forecasts and risk assessments in conjunction with one another

- Stronger guidance when interest rates are lower.

Meantime, we have been drawn to some comments from Howard Marks, the legendary investor, whose recent utterance titled ‘The Illusion of Knowledge’ and a link to the article can found at:https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/memo/the-illusion-of-knowledge

Marks explores the behaviours of decision-making and the forecasts of the financial sector that are routinely divided between those who say they ‘know’ and those who ‘know they don’t’.

The former: the absolutely certain macro forecasters are essentially those taking information in one end and spitting it out the other as something that can be banked upon. Dangerous behaviour that, in a world where certainty seems in short supply. To exemplify the point, all we really need do in the context of the last couple of years is ask, ‘Who could have predicted… [insert your own favourite unforeseen event]?’

Answer: nobody.

Those who don’t know the future and recognise that fact are capable of taking on board a range of inputs in order to make important decisions. There is, boiled down, no other reason for looking at forecasts or seeking to understand something about the macro future. However, in developing models of future activity decisions must be made on the variables to be included and the level of dependence upon each other. This requires value judgements and the more variables involved the compounding effect of any inaccuracies. It could be suggested we search not for the numbers but for the story that makes most sense to us. There is confirmation bias built into that approach argues Marks (and we agree with him). So, a single forecast on any matter, from a central banker or anyone else, is inadequate for good decision making.

To emphasise this point, at the outset of his missive, Marks quotes one of the twentieth century’s great economists: JK Galbraith:

“There are two kinds of forecasters: those who don’t know, and those who don’t know, they don’t know.”

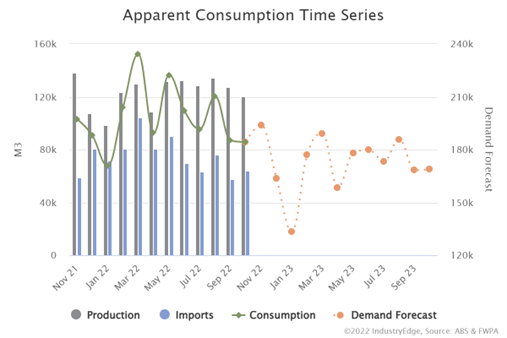

As an industry example of just one input into forecasting, IndustryEdge, one of the collaborators on Statistics Count, provides a forecast of sawn structural softwood consumption to its subscribers each month. The forecast is based only on housing and prior consumption data (including the public-level FWPA sawn softwood sales data) and provides a consumption forecast that goes out just 12 months.

The most recent forecast – up to October 2023 – is displayed in the chart below.

The value of IndustryEdge’s simple forecast for each of the subsequent twelve months is it translates the housing trend into a sawn softwood consumption trend. IndustryEdge says the numbers matter less than the trajectory and pace of change it points to. The forecast is merely guidance. It also says that if any month’s consumption was the same as forecast a year earlier, it would be nothing more than a coincidence.

There are other and similar examples.

We might say that ultimately, like the manner in which they are constructed from multiple inputs, forecasts are just one useful input into what is ultimately business level decision making. You can, perhaps, outsource the forecasting, but few businesses will outsource the decisions.