December quarter economic growth (GDP) was up 0.5% and has lifted 2.7% over the full 2022 year. The result seems to be an indication that the RBA’s program of interest rate rises that commenced in May 2022 are starting to do their anti-inflationary job.

At the end of 2021, annual GDP was running at 4.6% and the December quarter had just clocked 3.7% alone. That was the tail end of the pandemic’s direct effect, as inflation was starting to move up. As inflation lifted, stimulated by an economy jammed up with demand and spending power, it was inevitable interest rates would rise and place downwards pressure on demand and by extension, economic growth.

The judgement as to whether economic activity has eased enough to curtail demand and reduce inflationary pressures will be the subject of speculation ahead of the next RBA meeting in April. The pundits are divided. There are those who think a ‘pause’ in April would be welcome and others prefer that to occur in May. None expect the cycle to be ended, though the end of increases in official interest rates appears nigh.

As Gareth Aird from the Commonwealth Bank told The Age’s Ross Gittins, “There is a key risk now that the Reserve Bank will continue to tighten policy into an economy that is already showing sufficient signs of slowing.”

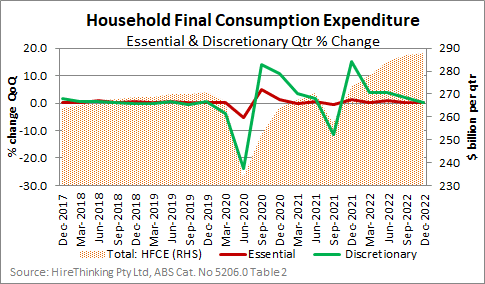

Anyone sitting around the kitchen table will not be surprised to see the impact of the ten consecutive interest rate rises since May 2022 showing through in significant declines in growth of household spending.

Higher interest rates and therefore increased costs – especially for home loans – are biting for many in the economy. The sole option for many is to reduce their expenditure.

There was a major uptick in household spending as the people adjusted to post COVID living with household spending up 6.3% in the December 2021 quarter and discretionary spending up a massive 15%. Move forward twelve months and the cash rate is up from 0.1% to 3.6%, leading discretionary spending (the green line) to all but stop in its tracks, growing a modest 0.4% in the quarter.

Meantime, while wages have grown, they have not kept pace with increases in household costs. Real wages are going backwards and that is likely to be a long-term issue for growth in the Australian economy. We might recall that prior to the inflation and interest rates vortex, the RBA and others were spruiking the need for wages to increase to sustain economic growth. We can be assured that in the next year or so, that conversation will again be front and centre, because it is an enduring structural issue.

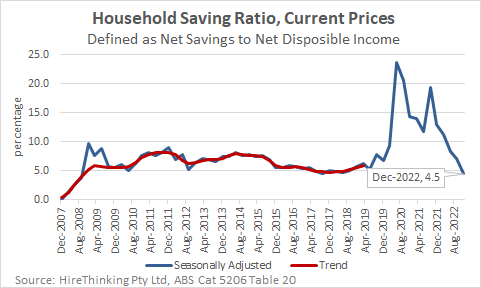

The consequence of a real decline in household income is that the modest growth in household spending has been funded by a further reduction of household savings. Household savings have fallen from a peak of 23.6% in June 2020 to 4.5% in the December quarter.

This is an important indicator for the RBA as it considers interest rate rises. It now appears the rate rises have soaked up spare household capacity, represented by savings. With the lag effect, the risk is that further interest rate rises will tip the economy over, potentially into recession.

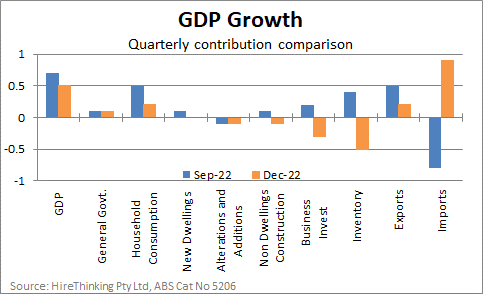

The impact of the reduction in demand can be seen in the changes in the contributions for growth for the quarter.

Business investment is down, inventory growth has slowed and ironically the positive contribution to growth from imports reflects the reduction of import volumes during the period.

Significantly, for the housing industry, the impact of the interest rate rises is very evident in the contributions to growth. New Dwelling investment was flat (0.0%) and Alterations and Additions were down -0.1%.

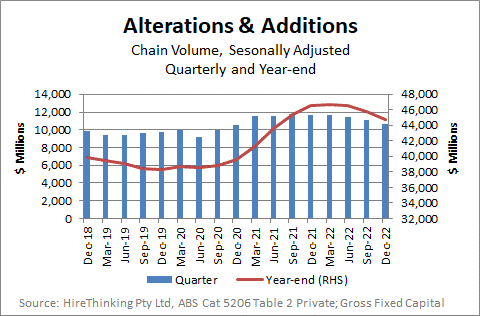

In dollar terms, the December quarter was the sixth in succession in which Alterations & Additions declined from a quarterly peak in September 2021 of $11.803 billion, to $10.616 billion in the December quarter.

So, while these are all signs the economy is slowing inflation, the annual inflation rate for February was 6.8%, down from the annual rate of 8.4% reported in December. This was still well above the RBA’s target range of 2-3%. (Read more elsewhere in Statistics Count)

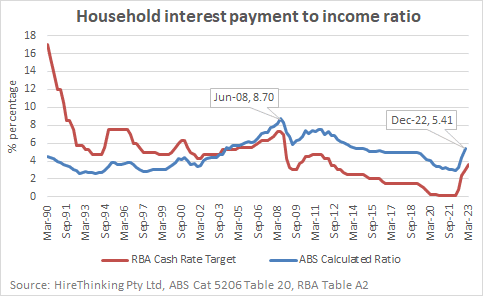

Its also important to note when considering the trajectory of interest rates that at a macro (economy wide) level the ratio of housing interest payments to household income has jumped up significantly to 6.33% in the December quarter. However, as can be seen in the following graph this is still lower than the peak of 8.70% reached in June 2008 when the cash rate hit 7.25% and annual inflation peaked at 5.0% in the next quarter.

It is undeniable that the rapid increase in interest rates is having an impact. However, due to the lag effect of how these measures flow through the economy, it is still not clear that the inflation tide has turned, or whether it is declining fast enough to keep inflationary expectations anchored within the RBA target range of 2-3%.

Coming from a great height, that is a fairly precise target point on which to land and hold. The counter risk is they drive the economy into the ground, by over-shooting the target.

We will know more following the next RBA meeting in early April.