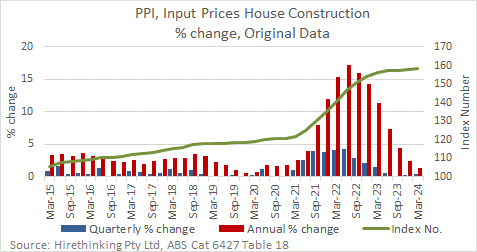

In a country that is determined to build 1.2 million new dwellings in the next sixty-two months, there are challenges in the latest Producer Price Indexes (PPIs). The PPI for inputs to the housing construction sector shows costs increased 0.4% in the March quarter, feeding into a 1.3% annual increase. Detailed data shows modest depreciation in prices for timber products however, while the cost of energy-intensive materials (steel and aluminium) lifted for the quarter.

The difficult and even inescapable news for the energy-sucking sectors of the housing construction supply chain is that their increasing energy costs are large enough for them to be passing them on, into the supply chain, forcing construction costs higher.

Due to demand, higher energy costs and labour challenges, structural concrete products also experienced increased input costs, impacting residential construction and general construction activities and costs. As the ABS observed, pressure is coming from activities like the infrastructure projects, which are driving demand for limited resources.

Although the annualised data shows housing construction costs have risen 1.3% over the year-ended March, that is a far cry from the parlous 17.3% recorded year-ended June 2022 – less than two years back!

The first chart shows how quickly housing construction costs increased, and how just as rapidly they have returned to more normal patterns of growth.

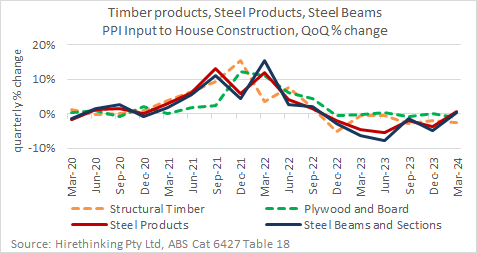

Compared to the energy-intensive products, timber products have moderated in price, largely due to the basic laws of supply and demand and without the barnacles of electricity and emissions costs to slow down their natural price movement. The consequence is timber products are more than playing their part in assisting with housing affordability, in the midst of the current ‘crisis’. We may wish that it were so for some other products.

In building materials, the main contributors to the rise in input costs was Other metal products (+0.5%), driven mainly by aluminium windows and doors (+1.0%), due to rising raw material costs, and elevated road freight costs in recent quarters, according to the ABS.

Partially offsetting the large increases were price falls in Timber, board and joinery (-0.5%), the driver for which was structural timber (-2.5%). This was reportedly due to elevated softwood import volumes and decreasing demand for new house construction. Presumably, the ABS means here that the overhang of inventory has been quit over the quarter, with modestly lower prices recorded.

The chart below shows the relative movements in input costs for the main products.

Though the trends are similar for steel and timber products, there are notable period where the price movements for them deviates. Importantly, the stability in timber prices over the last year is in contrast to the steel prices, which initially slumped and are now rebounding. External factors – many like energy costs, potentially being beyond the control of the steel producers – appear to create greater volatility.

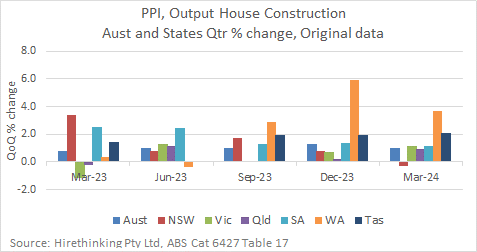

Its relevant to note the State based movement in house construction costs, which show increases in Western Australia and Victoria. The ABS reports that:

“Ongoing labour shortages for finishing trades, price rises for end stage materials, and the resulting cost escalations drove price rises this quarter, contributing to base price rises.”

This is an important point. It is difficult to get a dwelling finished because of labour constraints, in an economy that has very low unemployment levels.

Writing in The Age, Jemimah Clegg observed that housing construction costs rose in total by 10% in Melbourne, for example, over the year-ended January, reporting that materials and labour costs are causing builders to increase their margins for fixed price contracts, to cover the risks of over-runs. Quoting the Masters Builders Australia CEO, Denita Wawn, Clegg reported apprentice levels are down 25% over the last year and the number completing their trades also declining.

How exactly is this labour-dependent system of housing construction going to deliver an increased volume of housing and at the same time, alleviate costs? The simple answer is that it is not likely to do so, while ever there are so many high-cost, high-labour dependencies embedded into the supply chain.

The ABS continued, with the equally telling proposition that:

“Differing demand across capital cities impacted builders’ ability to recover and maintain margins, with increased demand in Western Australia resulting in higher prices. Increased bonus offers to attract new business offset base price rises in New South Wales, as demand for new house construction continued to weaken.”

That is, there are weakening prices for houses (in New South Wales at least), while input costs are still rising and there’s insufficient labour to do the work! What could possibly go wrong there?

Speaking to the Australian Financial Review’s Nick Lenaghan, the chief economist at Knight Frank, Ben Burston said:

“…the spike in construction costs is the most binding constraint and has dissuaded many developers from initiating a more robust supply response over the past year despite rapidly rising rents.”

That speaks to builder’s margins and effectively undermines the demand-side pressures being applied by a growing population.

Where is that price pressure coming from?

In part, its materials costs measured via the PPI. But just as significant, it is from labour shortages and that cannot be resolved by cutting materials costs. It’s a system of work issue that is very difficult to resolve.