Australia’s unemployment rate sat at 5.7% on a seasonally adjusted basis, at the end of July 2016, returning to its lowest point of the last three years. 725,500 people were out of work (among those seeking employment) in July, approximately 5,500 less than a month before. At first glance, that’s a good result, but look a little deeper and the employment data presents some worrying trends.

Seasonally adjusted unemployment data is displayed in the following chart, which indicates the number of people who are unemployed has been falling, as is the percentage of those looking for work.

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

The headline unemployment numbers look good in the above chart. They are headed in the right direction. But to a gain a full understanding, we start by examining changes in the number of people in or actively seeking work, known as the ‘participation rate’.

The participation rate remained at 64.9% in July, more or less the midpoint of the range of participation rates over the last five years. That is to say, more people could join the ranks of those seeking work, but equally, some could drop out. Meanwhile, the jobs that are growing are not all they are cracked up to be and they are competing for very few additional hours of work (up just 0.06% in July, on the prior month).

Writing in The Guardian, Greg Jericho described it this way:

“But even here we need to look at what type of employment is growing – rather than just the big overall number.”

“The monthly employment growth paints a less rosy picture than the 5.7% unemployment rate would suggest. After five months of full-time employment falling, in trend terms the growth of 1,239 people employed full-time saw a 0.02%increase.”

The trend towards part time employment can be seen in the chart below. Total part time employment has grown to 3.817 million Australians in July 2016, 5% higher than was the case in July 2015.

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

It had long been held that the rise in part-time employment was the province and domain of women, mainly with children and returning to work. But the data, as Greg Jericho ably points out, does not support that view.

The next chart, taken from Jericho’s article, shows employment growth over the last year, on the basis of gender.

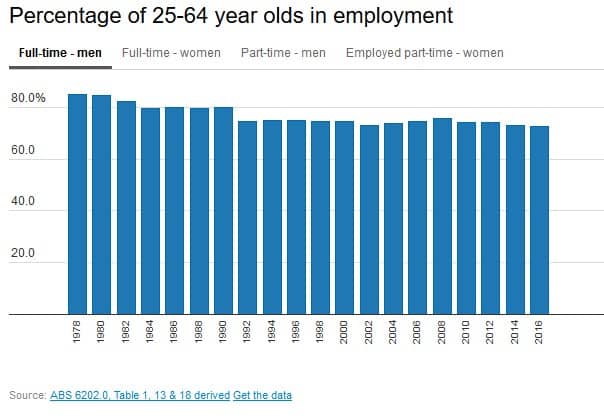

Of course, one year does not tell the story of a long-term employment trend. So Jericho deploys the next chart to show that the decline in male full-time employment is long-term.

Perhaps no one will be surprised, but we all ought be a little concerned that over the past year, the shift towards part time employment – and away from full-time employment – impacts the youngest the most, as the next chart shows.

Now for some, that will confirm long-held prejudices about young people and their commitment to work. But that’s all bunkum, as the next charts show.

The reality is that young people are (on average) losing their full time jobs and being jammed into part time jobs, while the same is also the case – but less so – for those aged over 65. The older cohort are getting about the same full time work as a year ago, but a lot more part time work.

Nothing demonstrates this more than the next two charts.

So, the sum of the last two charts is that the labour market is extending the total available work over a longer life-cycle of average employment, forcing an increasing number of participants to accept less work than they might otherwise like. With income generally linked directly to the number of hours a person works, there are potentially serious implications for living standards in the modern Australian economy.

What all this leads us to say is that an unemployment rate of 5.7% might look satisfactory at a headline level, but the nature of that employment and the structure of the economy supplying it, is fundamental to a proper understanding of the real employment market and how that impacts on society as a whole.

To bring that right back home, for those concerned about the future housing market, unemployment is a serious concern, and so too is underemployment, especially of those who we would all like to have as the next cohort of first-home buyers.