Its pretty hard to escape the ‘net zero’ language right now. Most of that is focussed on emissions and the middle of the century. But that is masking the other ‘net zero’, those who are treated as being employed, despite having zero working hours.

In September, Australia’s official unemployment rate was 4.6%, up 0.1% from 4.5% the month earlier. The headline data is good news and welcome, but as ever, its beneath the surface that we really have to delve to work out what is really happening in the employment element of the national economy.

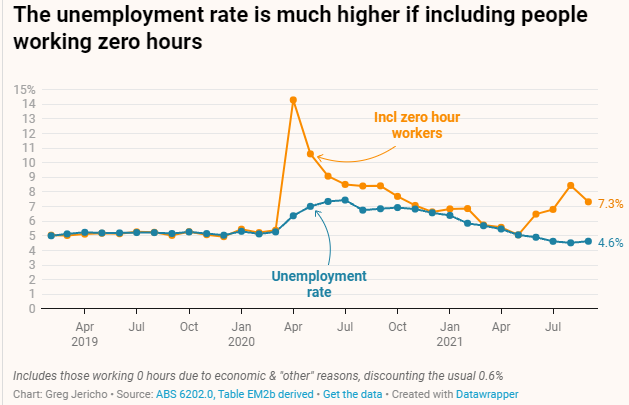

According to Greg Jericho, writing in The Guardian in late October, the real unemployment rate was closer to 7.3% because many people have a job but have had no shifts and worked no hours in the month. It’s a modern and unhappy phenomenon that is clearly linked to the pandemic and the lockdowns, as Jericho’s chart below shows.

There has been a remarkable resilience with employment in the last year or so, or at least, the economy has flexed up and down pretty responsively to the often-changing conditions. We can expect the zero hours experience to start to wind its way back out, especially as the weather improves, the shops open and the Christmas consumption frenzy takes hold.

Reflecting the zero hours worked the average hours worked per capita declined to 81.92 hours which was below the long-term average of 85.71 hours. If we apply some rough numbers, that means in September, the Australian economy did not use about 4.4% of the hours of work available to it.

If Australia was our companies, would we tolerate that? Could we?

But, there are also other signs that not all is well with employment.

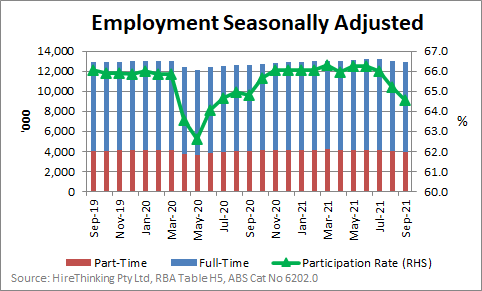

As the chart here shows, the participation rate continued to slip in September. Essentially, the participation rate shows those who are in work or actively seeking work. With a small rise in the unemployment rate, the number of people simply giving up looking for work continued to rise in September. At 64.5%, the rate is not yet alarming but could be better.

Overall, what the lower participation rate and the slight lift in the unemployment rate fed into was the number of people in work falling. In September, there were 12.884 million Australians in work, down from 13.022 million the month before.

When we put the unemployed and the underemployed (those seeking more hours – and we bet that includes the poor people on zero hours contracts), the labour underutilisation rate is 13.9%, as we see below.

To return the national economy to stable growth and equilibrium, effort needs to be applied to using our great productive resource – all of us. It seems this is a work in progress and one that can be expected to take up continuing attention as we unwind the last couple of years of economic disruptions.