Although limited in its intensity and potency, January’s rise in the Australian dollar’s exchange rate with the US dollar appears to have put paid to an early rise in interest rates in Australia. The rise of around 8% from early December to the end of January came about – as it so often does – because of global conditions, more than any Australian domestic factor.

In particular, the weakness of the US dollar – which given the apparent strength of the US economy is likely to prove short-lived at current levels – has played into higher commodity prices, which has helped keep the Australian dollar on an upward path for the last two months.

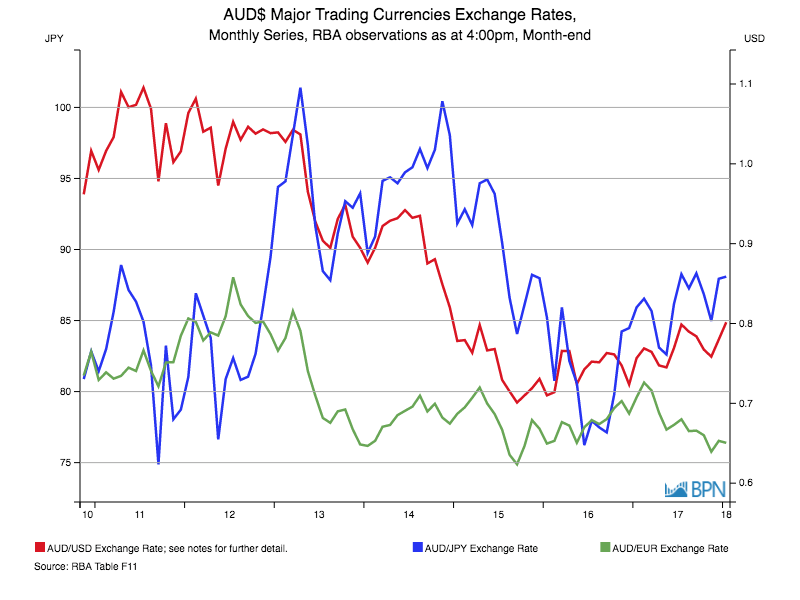

Although it is only a correlation, the chart below shows that the Australian dollar to Japanese Yen exchange rate is operating on a similar dynamic, but the same cannot be said of the exchange rate with the Euro.

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here

The pan-European economy continues in upswing, amidst what The Sydney Morning Herald’s Patrick Commins described as:

“…rapidly improving economic conditions [that] have fuelled expectations of a move away from extremely loose monetary policy conditions, including a potential for an end to quantitative easing.”

The European economy is; as Commins points out; still in an aggressive phase of quantitative easing or more open supply of money. It is languishing behind the US program of monetary policy tightening. That differential is flowing through into exchange rates.

The dilemma for the Reserve Bank of Australia is that a rising exchange rate is, by its own analysis, likely to lead to a slowing of the Australian economy, or at least a softening of growth, and prices growth, or inflation. Under those conditions, it is difficult for the RBA to commence increasing interest rates.

But, at the same time, US rates are rising, and at some point, even those in Europe will rise. Capital balances, especially for a nation like Australia that is somewhat reliant upon capital inflows, are disrupted by stubborn exchange rates.

This is not a disastrous situation for the Australian economy. Fundamentals are relatively strong and risks are moderate. But what is increasingly clear is that on a monetary policy front, the risk of suffering the unintended consequences of the rest of the world’s economic program are as present now as they were during the GFC.

The result of the recent speed bump is that Australian interest rates are now forecast to not commence rising until perhaps the middle of the year. Or not, as events will shape, and time will tell.