Australia’s Wages Price Index lifted 2.6% year-ended June, rising by 0.7% in the June quarter, to deliver three successive quarters of growth. The highest annual wages growth rate since 2014 has been recorded, but in real terms, against inflation, average wages continue to go backward. That’s a productivity issue and one set to get worse as inflation bites.

The chart below provides pretty clear indication the downwards trend has been broken, but the decade of malaise on wages growth has not been erased.

Source: ABS

In real terms – adjusted for inflation or spending power – Australia’s wages are in decline, or more specifically, continuing to decline. It is positive that wages increased in the private sector (2.7%) and the public sector (2.4%). The trajectory is right, but the pace is slow, especially with inflation running at 6.1%.

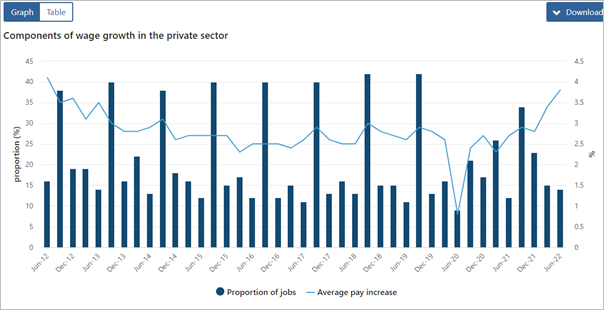

The next chart shows the stronger rise in private sector wages and the proportion of jobs in which there were wages increases in each quarter.

What the chart shows is wages increases across the private sector are going to a growing proportion of jobs – the June quarter data, compared to previous June quarters, provides that information.

That is welcome news, because a robust wages improvement in the economy would see sound increases spread far and wide. We are not there yet, but perhaps the corner has been turned?

Source: ABS

Whether it’s the recent report of the Productivity Commission (see the previous item) or the Jobs and Skills Summit (the item before that), the nation is debating how best to chart its future. People (labour resources) and how best to deploy them, are at the heart of that debate and wages are intrinsically linked.

As Michael Janda wrote for ABC News:

“In effect, that means workers took a 3.5 per cent real wage cut over the past year, as their pay packets were able to buy less goods and services than before.”

From a consumption perspective, wages growth drives capacity to pay increased prices for goods and services. If an economy has no wages growth it has no new financial capacity for its firms to deploy to make productivity improvements.

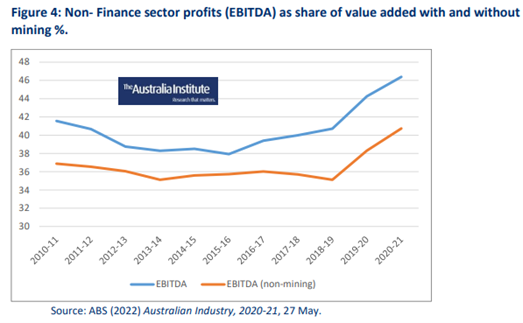

A long decade in which real wages growth has been difficult to find has coincided with very significant growth in mining sector profits in particular, as Richard Dennis from the Australia Institute told Janda commenting:

“What we’ve seen in Australia is a significant redistribution towards profit, particularly towards profit in the mining industry.”

He presented this chart to underscore the point about the role of the mining sector in particular in the profit versus wages share debate.

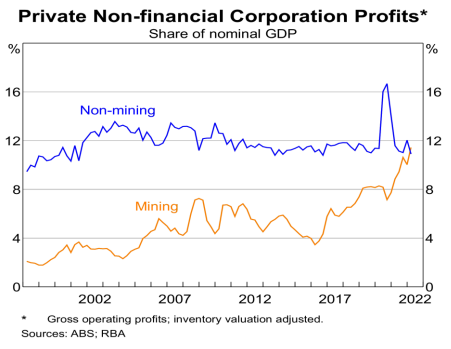

However, if you take out the finance sector also, as a share of GDP, the non-mining sector’s profits have not moved much, as we can see below.

We need to consider this carefully, because this is not profit as such, it is the share of economic growth taken up by profits.

What seems to be occurring is that other than mining and finance, profits are about the same proportion of total income for the Australian economy, while wages are stagnant. However, if we separate out the finance and insurance sectors, the most recent available analysis shows labour’s share of income (represented to most of us by the term ‘wages’) has been largely stable but has halved in the finance sector.

What all that means is that if average real wages are falling, there must be more people employed in those non-finance (and probably non-mining) sectors, presumably in firms or sectors that are not earning an increased share of national income.

To understand why that might be the case, read the previous item on productivity.

It is not our role to provide a solution to every conundrum, but Statistics Count can draw this much together: if the Australian economy is to grow at a stable and sustainable rate in future, it will need the value of consumption (goods and services) to increase consistently, requiring households to have more income from higher wages. The only pathway to that nirvana is productivity improvements.

Time to put the national thinking cap on.