Australia does not do enough with its labour resources, and has stagnated wages growth in an unsustainable manner. That is the conclusion to be drawn from the latest Australian employment and wages data.

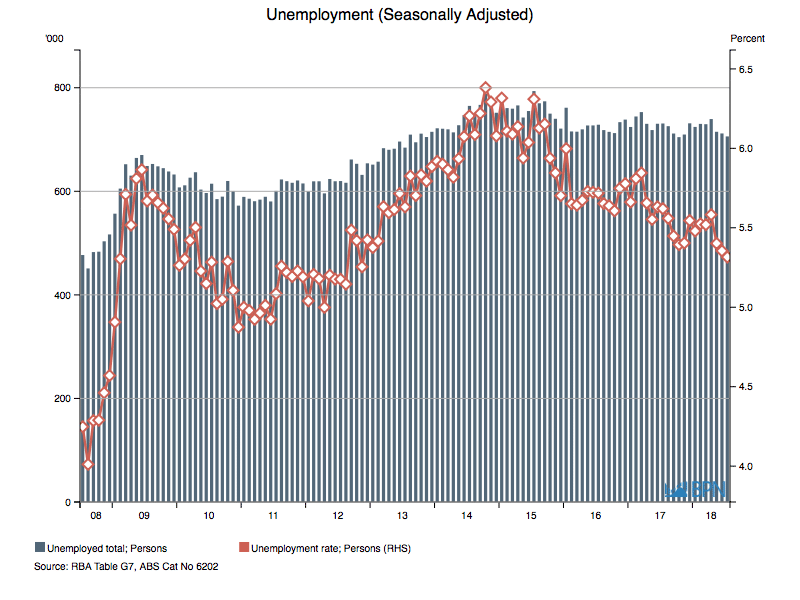

Despite the unemployment rate falling to 5.3% in July 2018, its lowest rate since December 2011, the critical concern is that labour is under-utilised.

It is important to note, as the chart below shows, that Australia’s 5.3% unemployment rate is by no means an historical low, although it is more than six years since the rate was this low.

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

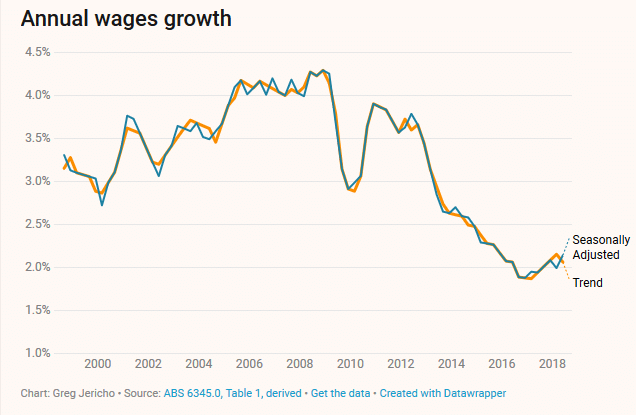

After plunging to long-term lows, Australia’s annual wages growth rate has managed to pick itself up over the last year – but barely. In real terms, as Greg Jericho wrote in The Guardian, wages are now standing still, but:

“…things don’t appear to be getting worse. The latest wages price data for the June quarter has wages for the public and private sector growing by 2.1% in both seasonally adjusted and trend terms.”

The chart below shows the slight improvements.

Wages growth is slow, at 2.4% in the public sector and 2.0% in the private sector over the last year. Jericho pulls no punches, saying:

“Annual private sector wages growth of 2.0% is pathetic – and lower than the 2.1% growth of inflation.”

Typically, we might expect that poor wages growth would be fuelled, at least in part, by higher unemployment. But that is not the case, despite the Federal Government’s Budget (new Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s 2018-19 budget) projection showing what appears to be unrealistic wages growth.

With employment high and unemployment low, wages should be growing faster than they are – or are likely to grow.

But why is that occurring?

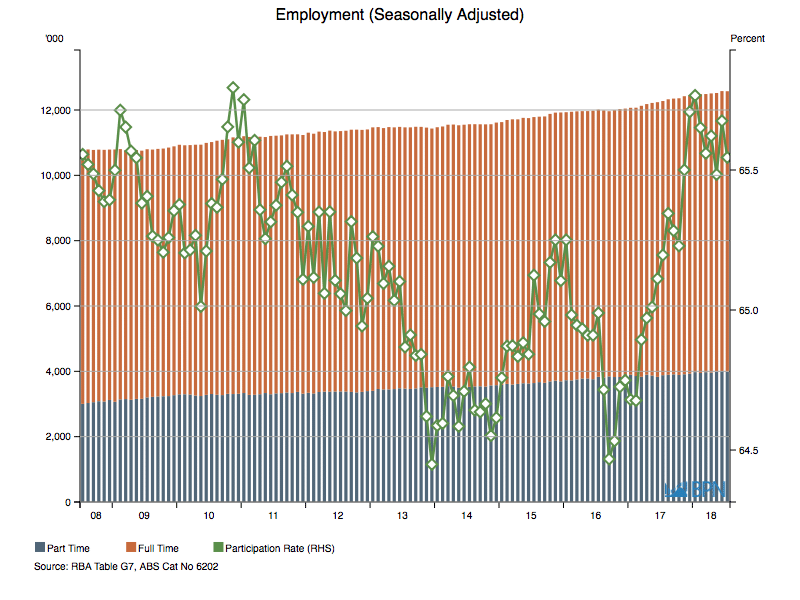

We can see below that the total number of people employed has continued to grow, and in fact, has grown relatively strongly over the last year or more. Interestingly, compared to July 2017, Full Time employment increased 2.7% to July 2018, but just 2.3% for Part Time employment.

At the same time, the Participation Rate (a measure of effective utilization of labour has essentially moved sideways, but improved just 0.5% over the year.

To go straight to the dashboard and take a closer look at the data, click here.

So, these headlines suggest that employment is going okay and that labour utilization is improving. But that isn’t so, as Greg Jericho has demonstrated in The Guardian showing that the majority of people who changed jobs in the last year did so to get extra hours:

“Over two thirds of those who changed jobs did so to change the number of hours – although only around a third changed from part-time to full-time or vice-versa.”

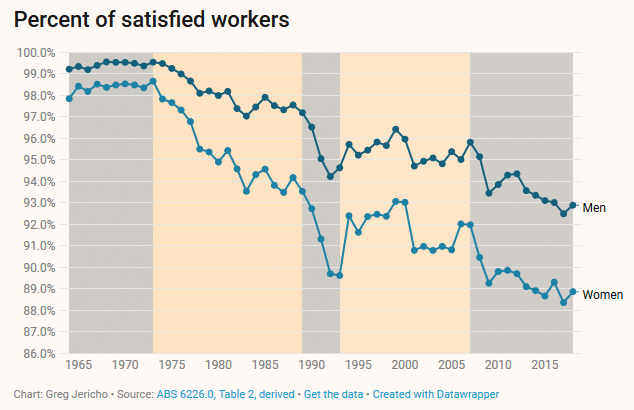

It is easy to see why this is the case for women, who dominate the part-time work landscape.

When we look at the next chart, it is not difficult to see that women want more hours and the absence of that feeds into deeper dissatisfaction with their work. For an economy that over the last fifty years has gained enormous advantages from deploying the additional half of its workforce, this is not good news.

Coupled with still unsatisfactory wages growth, the under-employment of Australia’s labour resources (people) is a potent driver towards longer-term economic malaise. Its another way to think of the productivity conundrum.